The Real Macbeth

In 2003 I was staying with a musician friend. He is a fan of poetry and I had given him a copy of The Lymond Poetry which he found delightful. He mentioned that he had an old newspaper article about the history of Macbeth by Dorothy and wondered if I'd seen it.

It turned out to be part of an old series called The Sunday Mail Story of Scotland, which was published in 1988 in 52 weekly parts. At that time the Scottish Sunday Mail was what might be called a “quality tabloid” and often contained interesting articles about the country, but I had no recollection of this series. The copies I've seen have been 32 page semi-glossy magazines priced at £1.

A look at the editorial board is revealing – there were three members: Gordon Donaldson, the Historiographer Royal for Scotland and a prolific author. Archie Duncan, who at the time had held the Chair of Scottish History and Literature at Glasgow University for 26 years. And our own Dorothy Dunnett.

Contributors included Prof. Ian B Cowan of the Dept of History at Glasgow University, and G.W.S. Barrow, Chair of Scottish History and Palaeography at Edinburgh University.

Part 4 contains an article by Dorothy called The Real Macbeth, and although it is aimed at a general audience and makes no reference to her own theories regarding Thorfinn it makes interesting reading for those looking to get an idea of the accepted theories of the time about this most maligned of Scottish kings.

At the time I made enquiries in an attempt to get permission to reproduce the article but the company that is quoted as the copyright holder in the magazine – The British Magazine Publishing Company – was part of the old Robert Maxwell group which collapsed after his death and is no longer in existence. I was unable to trace whether the rights were transferred to anyone else so I hope that there can be no objection to airing this article after such a long period of time on a website devoted to her work.

- - - - -

The Real Macbeth - an article by Dorothy Dunnett

Who was the real Macbeth? A power-crazy, murderous, yet weak man, as depicted by Shakespeare in his dramatisation, or a strong and able king, who ruled wisely and in peace for 17 years?

Ask most non-Scots to name a Scots king and they will eventually remember this fellow Macbeth, who murdered a kindly old man for his crown, egged on by his shrew of a wife who then went crazy and killed herself .

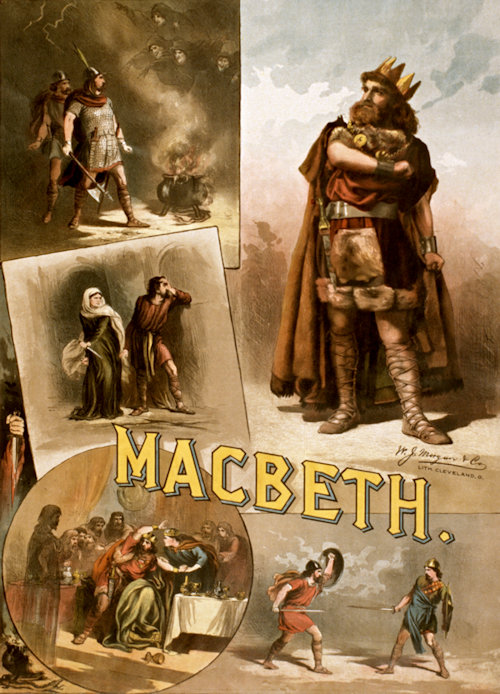

Orson Wells in the title role

It is small wonder that this story has all but smothered the true one. Since Shakespeare wrote his famous play (more than 500 years after the real Macbeth ruled) brilliant actors from Burbage to Barrymore, Garrick to Gielgud have persuaded thousands in a range of accents from American to conscientiously-drilled urban Glasgow that this was indeed a slice of actual Scottish history.

Actresses such as Sarah Bernhardt, Vivien Leigh, Diana Rigg and Judi Dench have brought their own ardour, ferocity and intensity to the role of Lady Macbeth on the stage.

This has all come into being because of Shakespeare’s play, not because of Macbeth himself. But because of the play, the real life of Macbeth has been obscured. The evil portrayed in the play has even come to represent a threat to those who act in it. Macbeth has long been considered an unlucky work with injury, fire and trouble falling in its wake. It is never named in the acting profession but referred to obliquely as ‘the Scottish Play’. When the superstition first arose is not known but some like to believe, even today, that the witches’ song still has the power of working evil. Investigation shows, none the less, that the witches’ song is an invention and that the true tale of Macbeth has nothing to do with witches or witchcraft at all.

The real Macbeth, who died in 1057, was not regarded as a villain in the bald monkish records that survive from his time. So far as one can tell, the legends surrounding his reign began between four and five hundred years after his death.

While Macbeth lived, his name as a warrior-prince must have carried some weight among the other rulers of the countries within reach of Alba, his Scotland. Because of its situation between Scandinavia, England, Ireland and the continent, Alba was a place of strategic importance. In Macbeth, it seemed to find a capable and imaginative king who held the throne in disturbed times for 17 years and was able, indeed, to leave his shores for a very long time without fear of upheavals behind him – something Edward the Confessor was never able to do.

Poster for an 1884 American production

In fact, Macbeth went to Rome – an event about which Shakespeare knew nothing. We know the date – 1050 – from the chronicle of an Irish monk writing in Germany; and we know that Macbeth was free with his gold when he got there, scattering his alms ‘like seed’ (as indeed was the custom in a ceremonial entry). He may have visited Rome as a pilgrim. His reasons were more likely to do with the benefits a Roman association might offer a country backward in development, which had hitherto relied on the care and protection of the Celtic pastoral Church.

Macbeth and his kingdom stood at the hub of a power struggle in which the Norse and the Danes, the Holy Roman Emperor and the Saxons of England, the Normans and Flemings and the Celts of Brittany, Cornwall, Wales and Ireland all played a part, with the pope in Rome courting them all. None of this could be guessed from the enclosed claustrophobic world Shakespeare created, for which he gutted a recent and unreliable history, ‘the Chronicle of England, Scotland and Ireland’, published in 1577 by Raphael Holinshead enhancing and twisting it, telescoping battles and years.

What did Shakespeare change? For a start King Duncan was not an old and wise man, even according to Holinshead. He was likely in fact to have been in his mid 30s or younger when he met his death on campaign, having spent the previous months in the disastrous attempt to capture the city of Durham in England. His grandfather had failed in this acquisition, and so did he. What drew him to travel from Durham to his death in North Scotland is not recorded, although it is most likely that his army went with him. Holinshead simply says that Macbeth, with the support of Banquo and others, slew Duncan at Inverness or another place which has never been fully identified. Shakespeare picked Inverness for the deathblow, but he was almost certainly wrong. John of Fordun, writing about 1385, says that Duncan was mortally wounded at Bothgofnane and was taken to Elgin, where he died. Bothgofnane – meaning ‘hut of the blacksmith’ in Gaelic – could be a number of places.

Macbeth’s wife is not linked with this killing. It was Shakespeare who introduced her as spur and fellow conspirator, and invented a murder that copied the killing of Duff an earlier King he had noticed in Holinshead.

King Duff, history stays, made his name at the castle of Forres. The killing was arranged by his host the captain, urged on by the lady, his host’s wife. Befuddled with drink, the royal chamberlains were blamed for it afterwards.

All this Shakespeare transferred to Macbeth’s time. Then he wrote a new role for Macbeth’s wife, his imagination fired by another reference in Holinshead. According to this, Macbeth’s wife ‘lay sore upon him’ to attempt to usurp the kingdom, ‘as she was very ambitious running in unquenchable desire to bear the name of a queen’. In fact, Holinshead lifted the reference himself from romantic history written about 50 years earlier by Hector Boece, who seems to have invented the lady’s fit of ambition, since previous writers say nothing of it.

Alas for Shakespeare, Macbeth’s wife appears to have been a loyal and blameless lady. From a previous marriage, she brought him a stepson, Lulach, who Macbeth seems to have cherished, and who was crowned king after Macbeth, before being killed in his turn. Nor was she ever called Lady Macbeth. Macbeth, meaning ‘Son of Life’ or ‘of the Elect’ is not a surname. The king’s wife would have been addressed as the lady Gruoch in Gaelic. The name is recorded in Fife where she and her husband are said to have gifted land to the Celtic monks of St Serf’s island, Loch Leven.

And what about the witches? Holinshead had already written about three women ‘in strange and wild apparel’, who promised Macbeth the thanedoms of Cawdor and Glamis as well as the throne, and who informed Banquo that his heirs, and not Macbeth’s, would rule Scotland. The prophecies, according to Holinshead, drove Macbeth to think of taking the throne, and later to kill his friend Banquo. Developing this Shakespeare turned the women into the ‘secret black and midnight hags’ of the kind King James I, his patron, had written about in his volume ‘Daemonologie’ And so were created the chanting chrones with the cauldron who have become attached to the tale of Macbeth, adding to its superstitious horror and poignancy.

The earliest known Scottish history of Macbeth’s reign say nothing of witches. They only enter the story in a popular chronicle, ‘The Orygnale Cronykil of Scotland’. Written by Andrew of Wyntoun, Prior of St Serf’s, some 350 years after, this mentions ‘weird sisters’ who offer Macbeth the crown but quite different honours. Hence the present castles of Glamis and Cawdor have no connection at all with this part of Macbeth’s story – indeed, there were no stone castles in mid-11th century Scotland, only halls and fortifications of wood. Nor can the ‘blasted heath’ and the ‘witches stone’ beside Forres be anything but inventions provoked by the legend.

If there were no prophecies, and no evil Lady Macbeth, why did Macbeth killed Duncan and Banquo, if not to seize the throne and prevent Banquo from founding the royal line?

To begin with, Macbeth did not kill Banquo because Banquo did not exist. The invention of Banquo began, not with Shakespeare, but with Hector Boece, who produced Banquo and his son Fleance from nowhere. By linking Fleance with Wales and the ancestors of the Stewarts, Boece managed to eliminate the Stewarts connection with the Archbishop of Dol in Brittany – a tender point at the time when relations between the kings of France and Scotland were bad.

The creation of Banquo served another purpose. It disguised the fact that the line founded by Duncan sprang from an unorthodox marriage. Crinan, father of Duncan, was not only abbott of Dunkeld but very probably connected with the minting of money. It was even possible that he and Bethoc, Duncan’s mother, had had several partners in marriage. By the time Boece was writing, a much-married clergyman, who was also a professional moneyer, was the last person a king would want to claim as a forbear. (Indeed, so worried by this was one later historian, that he took the risk of proclaiming that Duncan’s son Malcolm was a bastard).

In Macbeth’s time, none of this would have mattered. Several hundred years later, however, both churches and Kings lived according to different standards. By the time of the Stewarts, no one wanted to remember that once, kingdoms had to be ruled by men who were war-leaders, and thrones fell to the strongest and most worthy, and not automatically to the first-born. In Macbeth’s time, when England was overturned by the Danes and later the Normans, bastardy had no importance at all in the choice of the royal succession, and order of birth hardly mattered. Many of the monarchs in Alba seem to have allotted a good deal of time to fighting and killing unwanted successors and rivals. If Duncan, as a weak king, challenged Macbeth on Macbeth’s own homeland and lost, the outcome was probably good for the kingdom. Only, by NOT killing his nephew Malcolm, Macbeth put his own future at risk. Duncan’s son fled to the English court, to be reared as combined hostage and puppet-king and to become, in time, the excuse for an English invasion.

That invasion, under Earl Siward of Northumbria, is the climax of the play, and again Shakespeare takes liberties with his source. According to Holinshead, Macbeth was defeated in battle at Dunsinane (in fact, a prehistoric hill fort on the Tay, seven miles north east of Perth), but fled to Lumphanan in north-eastern Scotland. There (says Holinshead) he was finally slain by the Scots lord Macduff, whose family Macbeth had caused to be murdered. It suited Shakespeare instead to have Macbeth beheaded at Dunsinane by the vengeful Macduff, thus bringing to fruition two other mysterious prophecies; that Macbeth would never die until Birnham Wood moved the 12 miles south-east to Dunsinane, or until he was faced by a man ‘never born of a woman’.

What was the truth? Holinshead and Shakespeare both got it wrong. There was no such lord as Macduff. In fact, Macbeth was killed three years after the battle at Dunsinane by Malcolm.

Contemporary writers thought of the battle of Dunsinane as being entirely the business of Earl Siward, backed by the English king Edward. Independent records (and the earliest historians) admit that Malcolm eventually slew King Macbeth, but later historians were more coy, and introduced the fictitious Macduff.

Both prophecies date from the chronicle written by Wyntoun, who probably got the idea from early Celtic and classical legends. It is more than lightly that the battle did take place at Dunsinane, a hill of some military importance, although there is no sign that it ever bore a stone castle.

It is known however that Earl Siward at once marched south to York, where he was to die the following year. Macbeth moved back to his own land in the north east and lived for a further three years, until Malcolm raised a party in turn to kill him and his stepson.

There is still much to find out about Macbeth. Holinshead and others attribute to him the institution of an enlightened code of new laws. They may be right, but Macbeth’s Scotland was a place without towns or proper markets or roads. His administration was clearly good for its time, but it needed later Norman-trained rulers and the help of the Church to develop what he had started.

Shakespeare wrote his great play, and analysis of what he wrote will occupy scholars for ever. For good or ill the character of Macbeth has been firmly established throughout the world.