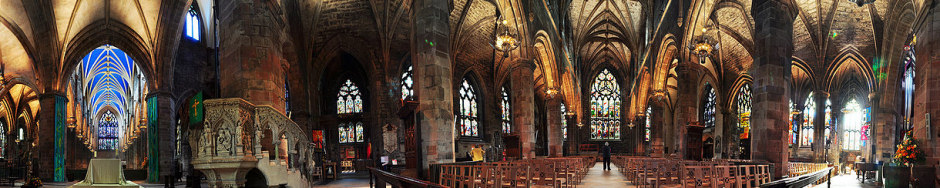

This is a transcript of the talk I gave to the April 2014 Dorothy Dunnett Society weekend. It’s a partner to the earlier talk on Marthe but was somewhat different in tone. For one thing it was longer, and I felt it needed more humour to lighten it up a bit. Secondly it followed two serious (though as it turned out excellent) talks in the morning, so again I felt there would be some need for a little light relief. Many people had expressed a liking for more quotations from the books so I included more of those and they needed the balance of the images in the second and fourth quarter to avoid becoming too much. Lastly there was no equivalent of the single word revelation which finished the Marthe talk. I hope I managed to find the right balance and gave Jerott his due place in the story, and that this version gives some of the feeling of the live talk.

Preamble

In my talk on Marthe two years ago I finished with this line

Perhaps the real tragic character of the series is Jerott, but that is another story.

That was meant as a bit of a tease and a way of ending the talk, but even then I had some ideas of a followup if that talk was well received. As it happened I had dinner with Ann and Kathy not long afterwards. Kathy was looking for speakers and she asked me if I would do another talk, and when I suggested her beloved Jerott she was positively ecstatic.

One Word describing Jerott

Before that talk I asked the audience to give me a single word describing Marthe. There were some rather …interesting… answers. Now I can’t offer you another one-word revelation of the type I gave that day, but I thought it would be interesting, given the conflicting feelings that her husband also generates, to see what today’s audience would come up with for him.

Let’s see what we have. Four terms appeared more than once

loyal (3)

insecure (2)

insensitive (2)

who? (2)

The rest are in alphabetical order:

| absolutist |

disillusioned |

magnificent and rude |

tenor |

| accommodating |

dogmatic |

mystery man |

tortured |

| angst |

emotional twat |

naive |

tragic |

| bemused |

gorgeous |

needy |

trustworthy |

| bewildered |

gorgeous and bewildered |

out-grown |

vacillating |

| brooding |

handsome |

overshadowed |

waste of space |

| complicated |

idealistic |

pillock |

well-meaning |

| conflicted |

immature |

robbed |

wooden-headed |

| deluded |

ineffectual |

sad |

|

| delusional |

inflexible |

sad & misunderstood |

|

| desirable |

intense |

self-delusional |

|

| determined |

lacking in empathy |

sentimental |

|

| devotee |

longsuffering |

solid |

|

| disappointed |

lovable |

tenacious |

|

Quite a varied selection! Well, as expected some of you adore him and would happily run off with him, and some of you want to beat him over the head for being thick. Probably there’s a few who want to do both! Some of you just feel sorry for him.

He does tend to polarise opinion doesn’t he?

Jerott Blyth is one of Dorothy’s most interesting creations and the source of considerable and sometimes heated argument. He plays a vital part in the story, but in some ways he’s also a tool used by the writer in order to allow us to get insights into our other principal characters. Today I’m going to discuss various aspects of his character.

What does he look like?

Let’s look at how Dorothy describes him – we’ll start with how he’s first introduced to us in Disorderly Knights

“…the stranger was unnoticed by the handful of knights kneeling with Blyth, and Blyth himself, his handsome black head bent, his only ornament the gold ring belonging to the dead girl he was to have married, looked distant and unlike the intelligent, talented and spectacularly wild young gentleman he had been.”

Intelligent – Talented – Wild

“It was nine years since their last meeting; and they had been boys in Scotland then, though old enough to fight side by side for their country. Of the two, Lymond, as he probably knew, had changed most since then. Nevertheless it was for only seconds that Jerott Blyth, Chevalier of the Order of St. John, stood, short, vivid, vital, and stared at the self-possessed stranger before him.” Then he said slowly, “Francis Crawford!” And darting forward, seized those cool, relaxed hands.

Short – Vivid – Vital

We see a passionate young man, with a history of being headstrong. Losing his father and possibly thrust prematurely into the position as head of his family – we never get any suggestion of an older brother – and then cruelly robbed of his wife-to-be. Presumably finding himself unable to settle to life in Nantes he joins the Order of St John. Seeking direction, but finding that the leaders he seeks are often weak and corrupt. He is full of contrasts – we hear him rail against the rule of the Order by de Homedes while at the same time holding to the idea that the Order is all that is holding back the Turkish empire.

“It’s a question,” said Jerott Blyth angrily, “of whether she will be kind to him. We’re a seedy, spiritless fraternity, as will be clear. A weak Grand Master and his clique may do with us as he wants. The best of us have been lost already through the Order’s mistakes, or through being dragged into Imperial wars under pressure, or because we’ve marched off home to our Commanderies, and de Homedes has had neither the guts nor the money to summon us back. And yet, believe me … there are great noblemen and great seamen among us still, serving their turn in the Hospital and ready to fight the Turk with their bare hands in between. We are the bulwark of Christendom. If we go, do you think the poor, ailing Emperor and his turkey-cock Doria and a scattering of ill-organized ships can take our place? The Sacred Law of Islam would span the known world.”

He was shaking.

So we see already that Jerott is a man of extremes but a man who is firmly on the side of right. We see hints of an experience of and therefore a desire for, a level of absolutism. For a black and white take on the world. Good and evil clearly defined.

He clearly finds in Gabriel something of the (apparent) integrity that he’s failed to find elsewhere. And of course Gabriel plays on that for a long time as he does with many others. But it seems he’s also immediately attracted to something he remembers in Lymond.

These lines:

“But he wanted to find, and give nostalgic credence to the attraction he remembered as a boy in Scotland, before the years in France and his joining the Order: before Elizabeth’s death.”

“Jerott had wondered now and then what the instant affinity had been that he had felt, nine years ago at Solway Moss, and whether, a man now instead of a boy, he would find it a childhood illusion.”

From the moment that he hurled himself, in a blaze of anger, on to Malta with his two hundred unfortunate shepherd boys, through all that followed, Jerott Blyth spent a good deal of time, out of curiosity, at Lymond’s side.

In this way we have the template set up for Jerott’s trials and decisions over the next two books. He will be torn between beliefs and between a pair of opponents who are everything in subtlety and in shades of grey that Jerott is not. One will manipulate him and one will fail to explain to him. His intuition will be sorely tested. But he does have intuition, as Dorothy is careful to tell us.

At one point Gabriel tries to ingratiate himself with Lymond

“I wish . . . you did not need to mock,” he said, and rested his fingertips briefly, as once before, on Lymond’s arm. “For of all men, my God could love you; and I, too.”

At the brief council of war held when the wall was almost completed, no trace of this encounter was visible to the naked eye, or even to Jerott Blyth’s lively intuition.

Jerott’s Attitudes and Moods

We’ve discovered early on that Jerott can be somewhat … moody, and sometimes hot tempered.

“That for the Order!” shouted Jerott Blyth, hurling the ripped shreds of his robe of St. John to the floor; and the circle of French knights about him, stirring, – murmured and looked at one another, and at Gabriel.

This is memorably reinforced at the beginning of Pawn in Frankincense, where, just in case we’ve forgotten, we get this superb description:

With Jerott Blyth, innkeepers never shirked the proper discharge of their duties. To the doggedness of his Scottish birth, his long residence in France and his profession of arms had lent a particular fluency. He was black-haired, and prepossessing and rude: a masterful combination.

If you weren’t already hooked before, you would be after that!

And this in the following chapter when he meets the Dame de Doubtance:

No one had ever been able to call Jerott Blyth a submissive young man. Violent in love, in hatred and in all his enthusiasms, he heard those words in a rising passion of outraged disbelief.

But we also know that he is extremely loyal. Loyal to the Order for a long time and loyal to his god, while his faith lasts.

Jerott stopped. “You tried on Malta to get Gabriel to revolt. He told you why he wouldn’t, and I’m telling you the same. It would be open revolt against the Order. It ‘would mean the end of us. I’ve taken an oath to obey. I’ll do everything humanly possible to change this policy of suicide, but if they won’t agree, I’ve no option but to obey. Don’t you understand?” He pushed the thick hair out of his eyes and glared, his sight thick with tiredness, at the bland, importunate face. “You follow the common laws of warfare, Crawford. Our service is to Christ”

And he’s loyal to his commander – whoever that is at the time.

Is Jerott an Everyman?

I’ve seen Jerott described as an Everyman, others have described him as an unreliable narrator. There may be elements of that but the character is far too developed for him to be just either of those things. Yes we see a lot of the story through his eyes, and he doesn’t always see clearly, but as we’ll see he sees more than many do, particularly once Gabriel is unmasked.

My feeling is that Jerott, as a character, is there to give Lymond a reliable balanced perspective, to keep him grounded and avoid him being lost in a sea of complex intrigue. I’ll return to that later.

Appearance – Jerott the Gorgeous

I suspect this is the bit that some of you have been hoping for and waiting for…

The men in the audience should maybe nip out for a drink for 10 minutes at this point 😉

Just as everyone has their own idea of Lymond’s looks, so everyone has their own thoughts on Jerott. So lets look at just how Dorothy describes his appearance.

We’ve already had Short, Vivid and Vital.

We also get:

Broader than Lymond and strongly made.

Beautifully built and hard as iron, Blyth’s compact body hit the sea side by side with Lymond’s;

From Kate’s point of view:

At the gatehouse Brother Jerott, with his curling raven hair and hawk nose over a beautiful Florentine cuirass, wasted no time.”Crawford of Lymond: is he here?”

Her sharp brown eyes sought and searched the brown face of this beautiful young man who had been kind to Philippa during that sickening episode of the old woman in the ditch

When he goes to Midculter with Philippa to tell of Joleta’s death:

Jerott Blyth took his stance by the windows, his thick, Indian-black hair flung back out of his eyes, his beaked, flaring nose jutting into the air,

On an earlier visit we have this:

“Jerott!” said Sybilla, and clutching with her two small hands as much of his worn leather chest as she could reach, hauled down his head for an embrace. She smelt marvellous. “All the most beautiful men become priests,” she said. “It’s an ecumenical law or something. I can’t imagine how they keep up the breed.

Even after 2 years marriage to Marthe and too much wine he’s described as follows when he meets his old colleagues just after a nervous reunion with Lymond.

This man Jerott,’ said Danny Hislop accusingly. ‘You said he was middle-aged.’ Jerott turned.

‘I didn’t,’ said Adam Blacklock indignantly. ‘I said he was stinking rich and cut his old allies dead in the street. I did not say he was middle-aged.’

Vivid, black-haired and muscular, with passions far from middle-aged lodged between the flat belly and lean hips on which he had just been insulted, Jerott Blyth looked at the two men and, for the first time, his face lost its apprehension.

Short – Vivid – Vital

Black-haired, and prepossessing and rude

Broader than Lymond and strongly made

Curling raven hair and hawk nose

The brown face of this beautiful young man

Kind

His thick, Indian-black hair flung back out of his eyes, his beaked, flaring nose jutting into the air

Vivid, black-haired and muscular

Do you get the feeling that Dorothy quite likes this character and wants us to think he’s pretty good looking!

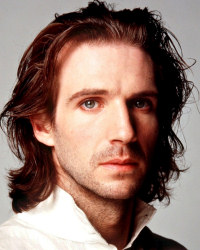

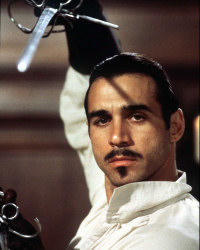

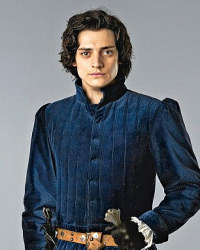

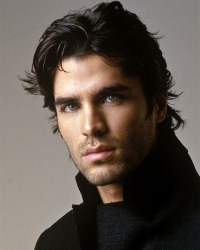

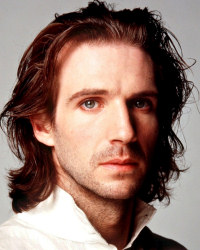

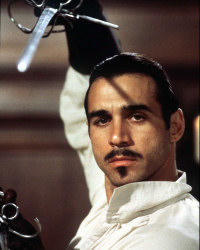

So how would all this translate into some of the film stars or models around now? Here’s some possible candidates to play him in the great casting game:

Ralph Fiennes

Not bad. The hair would need to be blackened but otherwise reasonably handsome

Adrian Paul

That moustache would have to go but he’s got the black hair.

Aneurin Barnard

A young actor with great promise for the part – three shots of him in quite suitable costume.

Could this be the face of Jerott?

Alain Delon

For those who were around in the 60s you may have good memories of this French heart-throb. Perhaps not quite dark and broody enough.

Personally I’m not so sure about the next guy but Kathy would never forgive me if I leave him out, so here we are:

Oliver Reed

The young Oliver is certainly handsome

But somehow I don’t see Jerott in this shirt!

I loved the caption on the website where I found this second one.

“Oliver Reed: One of the few men who could wear a shirt like this and still look like a hard bastard”

If you prefer the leaner look then how about

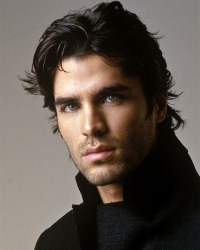

Ben Barnes

Would Jerott have a six-pack? – of course!

Bruno Santos

Slightly older and more rugged

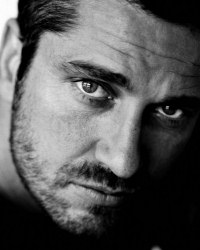

Gerard-Butler

Richard Armitage

maybe not beautiful enough but certainly does the moody bit pretty well

Rufus Sewell

has a number of fans amongst readers.

And finally, since I can see you’re all getting tired of looking at handsome young men, here is one I have no name for:

Unknown candidate

If you know his name then do let me know and I’ll add it here.

He’d probably be my own choice, as he seems to have a little of everything, but I’ll leave the ladies to make the final judgement!

Jerott the Sensitive – Awareness, compassion and sensitivity

Is sensitive a word you associate with Jerott? Probably not. And yet…

It’s Jerott who first meets Marthe and tries to prevent her from meeting Lymond. His sense of danger warning him that this girl who looks so like Francis must be trouble.

Then when he is the first to find the body of Oonagh in Dragut’s garden we see how much care he takes for his friend:

He had expected it, Jerott realized. He had braced himself hard against death, and for the reality he was quite unprepared. Jerott spoke, his voice steady. “She is more than dead Francis. If I thought you would do it I would beg you to go without seeing her.

and shortly after, when Lymond has seen the horrible straw-packed nightmare, Jerott offers to do whatever needs to be done with Oonagh’s body. If that isn’t compassion and selfless friendship then what is?

His pity and compassion for children is evident through much of the search in North Africa and for Khaireddin in particular when he strikes out on his own to find the child at the silkworm farmers house.

When he’s not saving his life it is Jerott who finds Francis in his extremes of fatigue or dispair and recognises what is wrong – in the pouring rain of the courtyard after Francis’ clash with Marthe when she tries to thrust him and Philippa together, and after the wild horseback ride in despair after the reminder of the men in the river it’s Jerott who realises that it is for want of Philippa that Lymond suffers his worst torments.

But of course he lacks some things – an appreciation for music for instance. It struck me while researching this talk that maybe there is something of the character of Gelis in Jerott, or rather the other way round. Just as there is the triangle of Nicholas, Gelis and Kathi, so we could construct two triangles of Lymond, Philippa and Jerott, or Lymond Jerott and Marthe.

Intelligence, and Occasional Lack of It

When he can use his brain analytically on a concrete problem Jerott is undoubtedly an intelligent man. And, he’s perfectly capable of changing his mind and realising that he’s missed or misinterpreted something.

To assemble these things faultlessly, and from a distance, meant some very high-power organizing indeed. It also meant a long purse – a startlingly long purse, even for a man with two homes and a comte of unknown resources abroad. Jerott Blyth at about this point turned a conjecturing look on Francis Crawford of Lymond riding easily at his side and wondered what else he had overlooked during these hot August weeks on Malta and Tripoli.

When he finally sees hard evidence of Gabriel’s wickedness he reassesses quickly. At Midculter:

“We understand now,” said Jerott Blyth bitterly, and turning faced her, his clasped knuckles, in a childish gesture, pressed on his lips. “I have been a thick fool.”

“I know. But there’s such a comfort in numbers, don’t you think,” said Sybilla, without really thinking.

He has his own resources for information too.

Jerott knew this. He also knew, from sources in Scotland, a little more than Lymond would expect about Georges Gaultier’s permanent house-guest.

When Lymond and Marthe rescue Jerott from the governor’s prison he’s in desperate condition – poisoned by cyanide gas and burnt from the fire. Yet he thinks clearly enough to follow the plan to get him released. (Lymond’s attitude to him is warm and concerned. Marthe too takes good care of him for the next period. ) During the interview with the Governor he is quick-witted and convincing despite being in considerable pain. He even deals with seeing Marthe in her magnificence as Maria. Moreover after they learn of the Peppercorn he has the presence of mind to invoke Leonne Strozzi’s name as the child’s father. This is not the thinking of some dullard – Jerott is a highly intelligent man.

It is Jerott who finds the Cisterns and deals efficiently with Marthe and Gaultier in doing so, after she rejects his request to go to Philippa’s aid.

It’s really that occasion on the ride to Dunbarton where he messes up, and of course we all remember it and it colours our other judgements and makes us think that he lacks intelligence. When he assumes that Francis likes being a soldier and gets the diatribe where Lymond tells him all the things he misses – finishing up with music, and he just doesn’t get it.

But that’s a fairly isolated case despite Lymond occasionally calling him an ass when he doesn’t quite live up to the master’s level.

Jerott the Soldier

As a soldier he is extremely talented and efficient. We hear him described by as good a judge of quality as Alec Guthrie who says this to Adam when talking about Lymond:

Why take Gabriel at all? He had to, my minikin fiddler with chalks; he had to, or he would have lost all his best men including Jerott Blyth who one day is going to be nearly as good as himself.

His grasp of strategy and his personal fighting skills are seen again and again.

Jerott Blyth himself was a thoroughly competent commander. The list he put before de Vallier of the work done and still to be done, the assessment of man power and stamina, the list of the weak to be rested and the strong to be conserved, was the result of long training, high skill, and a love of his work that lessened, he knew, the love he should pour upon his Maker.

When he returns to soldiering and stops drinking he soon regains his former abilities. Here we see his capacity for hard work and his military efficiency. And we see him compared to Danny who had replaced him in Russia and we’ve seen to be a fine soldier.

For a week, Danny was out every night, sometimes with a company of Germans; sometimes with Swiss. Jerott was allotted longer expeditions: at one point he worked out of Amiens with de Lansac for almost two days, and got back to Compiegne with a graze from a hackbut ball that killed his horse under him. He was thankful to find that Lymond was off with a party of German pioneers, doing something inexplicable with a couple of carts spread with tarpaulins.

Jerott had his scratch dressed, slept for six hours, woke, ate and discovered that Lymond had returned and left again for Peronne in the interval, leaving fresh instructions for himself and Danny. A quarrel about precedence had broken out among the German officers and he marched in and settled it, meeting Danny on his way out to collect a new gelding. He had not lost the ‘knack of command, he was pleased to discover.

Danny, who looked hollow-eyed, said, ‘Have you heard? He’s made the wells of Le Catelet undrinkable. Originality at any price. The Swiss, in their Swiss way, say he knows how to take Dame Fortune by the hair. The Germans, in their German way, say if he wants to lead them again, he will have to bloody well increase their stipend. You know he had all the grain fields laid waste but kept the vines standing to gripe all the Spaniards? The rotten bastard. If I were St Michael I’d disown him.’

Jerott, who was saddling his horse, did not bother to look up at the limpid eyes and teased sandy hair, waning from the baby-pink brow. He was beginning to get the measure of Danny. He said, ‘Where are you going?’

‘To take some culverin this side of Noyon, and then fall into bed for a lengthy four-minute sleep. I wish I’d stayed in Lyon. I wager Archie wishes he’d stayed in Lyon.’

Jerott mounted. ‘We all get out of condition at times,’ he said; and moved off at a brisk gait to where his troop of soldiers was waiting. Danny, gazing after him critically, was aware of a twinge of approval. He hoped that nothing about him revealed it.

Jerott the Drinker

It is with alcohol that we see Jerott’s real achilles heel. Firstly we see that he’s inherited one of Scotland’s less admirable traits – the drinking culture. Ironically he initially thinks he’s better at handling it than Francis is.

Blacklock, raising his brows, looked down at his long hands. But Jerott Blyth, a glint in his black eyes, watched Lymond. Last year in France, he well knew from the gossip at home, Francis Crawford had nearly wrecked his career and succeeded in poisoning himself with unbridled drinking. In Malta he had been moderate. Here in Scotland he had stopped drinking completely; taking no risks, it seemed clear, of being led into excess. It roused in Jerott, who had perfect self-discipline, an emotion of purest contempt.

However, even drunk, Jerott can handle the military and political implications of what Lymond is doing, it’s when personal matters come up that he loses track. In this passage the conversation moves to Philippa’s and Marthe’s separate attempts to keep Lymond in France rather than go back to Russia. Their conversation, loaded with undercurrents, baffles him.

Lymond paid no attention. He relinquished the edge of the table and moved gently forward until he stood over Philippa, his hands clasping one another behind his straight back. He said, ‘I hit you once, on the jaw. Do you remember?’

‘Yes,’ said Philippa. She added, ‘You hit me another time, on the arm.’

‘Oh? I had forgotten that,’ said Francis Crawford. ‘Why?’

‘It happens all the time,’ Philippa said courteously. ‘I was where someone didn’t want me. If they place the sun in my right hand and the moon in my left and ask me to give up my mission, I will not give it up until the truth prevails or I myself perish in the attempt. Are you going to strike me?’

‘I am considering it,’ said Lymond. ‘Jerott is now convinced I am corrupting you. Fortunately I know, if Jerott does not, when you are speaking from conviction and when you are being deliberately and spitefully obstreperous. You have never made any arrangements outside marriage and you have no intention of making any, even if I felt constrained to break my agreement and start back to Moscow tomorrow.’ He lifted his eyes to Jerott. ‘The Somervilles,’ he said tartly, ‘are adept at sheer, bloody, domineering interference.’

Jerott sat down. He said, ‘I don’t understand’; and then, after a moment,

‘Christ, Francis. Have you got into the Marechale’s bedroom already?’

The real problem of course is with Marthe. She is everything he wants and everything he can’t handle. When he can’t communicate or when she responds with wounding and sarcastic remarks he despairs and turns to drink, which just draws more of the same. It is his misfortune that his two weakness – emotional inexperience and alcohol combine so disastrously.

Eventually it is only Lymond who can pull him together and give him the purpose he needs but even then a meeting with Marthe can see him relapse.

Danny Hislop, irritated and envious, had made a few attempts through the keyhole to bring him to his senses, aided latterly by Adam Blacklock, newly returned from his duties in Lyon. Neither of them was present when Lymond kicked the door down, although the roar of the preceding musket shot brought them to their feet. What happened after that was mainly inaudible but Archie, questioned afterwards, conjectured that Mr Blyth had lifted his hand to his lordship, and Mr Crawford had knocked him down and kept on knocking him down until Mr Blyth was so beside himself with rage that he was nearly sober. Then Mr Crawford had thrown a bucket of water over him and told him to sit down while he told him a few things the Order forgot to mention.

Jerott the Passionate

Given his age when Elizabeth dies it seems likely that she was his first love, and we don’t hear of any others prior to his joining the Order, at which point he takes vows of chastity. He’s described as being “violent in love” but we must conclude that this is a more general description of his wider passions.

Once he leaves the Order and returns to Scotland he’s free to allow his feelings freer rein but he’s certainly not indiscriminate, nor is he always misled by beauty:

The meeting between Lymond and Tom Erskine’s widow took place in private. Jerott, who had no interest in Lady Jenny Fleming, however pretty and however famous as the King of France’s second-string mistress, set about getting the wagons loaded and the oxen hitched.

However when he sees someone he really likes he is captivated. For instance when he sees Joleta for the first time:

A small, choked sound came unawares from Jerott Blyth’s throat. Lymond’s arm brought him up short. “Control yourself, Brother. A peach, I agree, but a dangerous peach. Let me deal with it first.” And removing his hand, he melted into the night. Jerott took a step forward, and then a step backwards; and then stayed where he was, a handful of thorn in one fist. He was shaking a little, as one did when the cathedral doors opened and kneeling, one felt the bearers brush by in incense, and saw the still, loving smile of the saint.

His eyes were wet. And, God in heaven, his right hand was covered in blood. Pulling himself together, Jerott Blyth released the thornbush, jerked down his leather jacket, drew his sword, and took a professional step forward again.

Shortly afterwards he takes her, fainted, to Midculter:

When, under the direction of a stalwart Venetian madam to whom he took an instant dislike, Jerott placed his childish burden tenderly on her bed, Joleta was still unconscious. Her skin was so fine, he saw, that the veins ran like Sicilian marble over her temples and jaw. From her thinly framed nose to her invisible eyebrows, her sparely moulded pink mouth, her prodigious golden lashes, there was nothing coarse about her; and her hair, blown lightly on the lawn of her pillow, was insubstantial as new-loomed silk.

However when Joleta fights with Lymond he bursts in and tries to play the chivalrous rescuer but is baffled by the reaction:

Jerott had not heard. He was staring, like a man in a nightmare, at the vanishing figure of his dream.

It’s not just women that bring out his passionate side either. Once he is committed to the search for Gabriel he becomes equally passionate to the point of forgetting to think things through:

‘We are surely agreed,’ he said, ‘that Graham Reid Malett must be found, and when found, must be killed. He’s evil; he’s dangerous. He’ll never forgive us for what we did to him in Scotland. He will certainly kill you if he can. . . .You know what else he can do. I demand,’ said Jerott staunchly, ‘to take my share in the execution. I am staying. And if you think you can make Philippa go back to England, good luck to you. It’s more than Guthrie or I managed to do.’

At least on occasions he’s aware of his failings, and vehement that he will not repeat them – as when he speaks to the Dame:

Then Jerott Blyth said, ‘Then you must put on record that once I loved a girl and wished to make her my wife; and once I loved a man and wished to make him my leader. I shall never do either again.’

… Yeah, Right.

But of course with Marthe he is on totally uncharted ground. The most experienced and emotionally mature of men would find her a difficult proposition.

Jerott and Marthe

Marthe is Jerott’s delight and his greatest trial – the source of all his frustration and confusion.

Not surprisingly he’s attracted to her almost from the beginning. After she helps save his life by masquerading as Maria he starts to recognise his growing love when they are imprisoned in Guzel’s home.

But his confusion over that love, clashing with Marthe’s unhappiness, both in general and at Guzel suggesting him as a possible husband, mixed with his revulsion at any suggestion of homosexuality, either in his own feelings or in Lymond’s actions with the Aga, leave him ill-equipped to handle or understand the clash between Lymond and Marthe when Lymond finishes by kissing her. He longs for the straightforwardness of fighting and the chain of command. But how many others would have fared any better?

And as an aside – in his anger he gets it. The magnificent display on the horses and the escape through the back of the Aga’s tent. And here in action again, we find him at his best.

Jerott, well fed, well rested, fully recovered from his fever, was a natural horseman, with the horseman’s broad shoulders and strong, capable hands. The beautiful little Arabian mare between his knees answered him like a polo pony: horse and man might have been one.

After the escape, when the party split up and he and Marthe separate from Lymond, they are thrown closer together.

Jerott had come to terms now with the fact that one man could make him feel and act like a rhinoceros in a cloud of mosquitoes. Marthe had not perhaps quite the purely detached ability to hurt which Lymond exercised with such care. But with Marthe in every other way it was far, far worse. The eyes, the mouth, the brain, the body through which she expressed her indifference and her contempt were those of a woman he wanted. A woman high, cool, remote as a cloud forest, trailing mosses and bright birds and orchids; a woman with a body like moonlight seen through a pearl curtain. A woman whom he had not touched since, her sardonic blue eyes studying him, she had said, ‘You only want me because…’

It would be bad enough if it was just indifference, but it’s not. Marthe is also in some turmoil. She distrusts men in general and the male world that she sees no place within. Her only source of something resembling love up to now has been Guzel, but Guzel has other fish to fry and has told her to consider Jerott as a possible suitor. She is in the throes of a battle in her own mind whether she can accept that suggestion or reject it utterly. She’s involved with Gaultier in a scheme to make money, something she needs to be able to claim a place in society, but she hates him. She’s also conflicted about Lymond and what he represents. So of course her anger and internal conflict find an easy target in Jerott. Something he is as yet entirely unaware of and ill-equipped to understand.

But still there are flashes of wonderful potential to inspire him:

And at his side throughout, there was Marthe . . . quick-witted and intuitive, articulate and thoughtful. He had loved her for her beauty and for an excellence with which he was already familiar. That day, engrossed together in the fate of the child, he met her mind to mind and fell in love with her, with every grain of his spirit and cell of his body; with the essential finality of death.

Once in Istanbul she and Gaultier work to find the lost treasures and when Jerott asks her to visit the Seraglio to take a message to Philippa she refuses. And his anger boils over.

He took the flat of his hand across her face then: the hard, soldier’s hand, which made an impact like the sound of the breaking of sticks, and left her fine skin staring livid; and then colouring fast with bruised blood. ‘I hope,’ said Jerott, breathing softly and hard, ‘that you never meet those who will judge what you have done. How would you recognize love? Or compassion? Francis at least has learned that. You avaricious little slut… do I call in the Janissary; or will you do as I say ?’

Her face was unflinching as a tablet of stone. ‘I shall do it,’ she said. ‘Since I must, to be free of you. Go then and find you a whoremonger. What use to you – any of you – is a mind and a soul, when all you need is a body?’

There was a silence. ‘You didn’t ask,’ said Jerott at length. ‘But I would have forgone even the body for the sake of the mind. And I would have claimed neither body nor mind, had I discovered a soul.’

After the chess game and the flight to Volos they are reunited in their attempt to save Lymond and Marthe’s success in leading Francis through the worst of the pain brings his admiration. Marthe herself accepts that men can in fact be as moral and kind and honourable as women “…you are a man and you have explained all men to me.” and finally she accepts Jerott’s love.

In Checkmate however things have turned for the worse. Jerott puts her on a pedestal and tries to provide for her instead of working with her to advance her knowledge and interests so she can earn her own independent place in society. Clearly the communication essential to marriage breaks down and in despair he turns to his one big weakness, drink.

As he once did with Lymond, he distrusts her motives, and despite advice from Francis he fails to understand her, returning to soldiering, and eventually leaves her when he believes, wrongly, that she has forced Phillippa away.

Jerott the Brave

We see plenty of examples of his bravery, often in extreme circumstances:

He works with Lymond to prevent the fuse reaching the gunpowder in the arsenal; courting almost certain death.

At the last door even Jerott hesitated. The lit match must now be so near the powder that a breath would dispatch it. ‘ The opening of this door in his hand was his entrance card, at twenty-five, to heaven or hell. The bolts were drawn. He remembered to pray for the first time, briefly and even with shame, and drew the door open.

He goes into battle at Zuara with a broken wrist, loosely strapped. The pain of that must be enormous.

He then rescues Lymond from the bottom of the sea with that same handicap, and pulls him to safety one-handed.

He tries to rescue Kedi and Khaireddin at the house of the silkworms and fights for his life in the fumes.

Unlike Francis Crawford, whose game with life was a strange and rootless affair played with the intellect, Jerott had a passionate instinct to live. It was a happy circumstance also that his nervous and bronchial systems were roughly as frail as a bison’s.

He rescues Lymond from the river Authie after the floating mill is crashed into the bridge.

As we’ve heard, he is nicked by a musket ball which kills his horse and shrugs it off as if it were nothing.

If bravery is the mark of a hero then this man has it in spades.

Jerott and Lymond

Lymond’s opinion of him and feelings towards him

Lymond usually hides his feelings and doesn’t bestow compliments easily so we should take notice when he does.

From the council of war at Boghall:

But for Adam, who hid her for me, the whole sordid business would have been exposed there and then, and to Jerott, Gabriel’s adoring disciple: poor bloody Jerott, torn in two. . . . He was to be Gabriel’s Baptist and oust me before he came, did you realize that? Luckily Jerott is an intelligent man as well as an honest one, and it didn’t happen. One of the things I have promised myself is to get Jerott out of this safely.”

At the end of Disorderly Knights:

“They ask more than anyone can give,” said Lymond, his manner suddenly altered, and got up. “Is this true? You see beyond Gabriel’s shadow to the ideal of the Order? And beyond mine to … what I mean to do, rather than what I do?” He smiled, though not with his eyes, and coming forward, stood with Jerott in the doorway. “You will find your place, Jerott. Good luck. And God speed you to France.”

He did not touch the departing man, nor did his eyes have in them any of Gabriel’s lucent candour; but Lymond’s voice was as Jerott had rarely heard it, pared of all mockery, and a little of the warmth he was suppressing, despite his effort, showed through.

And for some reason, this brought Jerott’s whole mechanism for speech, emotion and deed to a shuddering halt. He stood, his stomach turning within him, and heard Lymond add, his voice cool once more, “How unimpeachably shifty it sounds. What a fate for the tongues of the world, that after Gabriel all that is true and simple and scrupulous should sound like primaeval ooze.”

It was then that Jerott took heed at last of the knot in his belly and the ache in his throat, and announced, regardless of every plan he had made, “I should like to stay. May I?”

“Oh, God, Jerott,” said Francis Crawford, and the blood rose, revealingly, in his colourless face. “Yes . . . but . . . oh, Christ I’m glad; but if you touch my back once again you’ll have to see the whole bloody thing through yourself.”

In Pawn in Frankincense:

There was a furious pause. Then Lymond’s voice, the chill gone, said, ‘Don’t be an ass, Jerott? You know I can’t do without you.’

It was an obvious answer. But it was also something Jerott had never had from Lymond before: an apology and an appeal both at once.

‘You put up with a lot, you know. More than you should. More than other people can be expected to do. … I find I need a sheet anchor against Gabriel. However much I try – don’t let me turn you against me.’

That, to me, is perhaps the key passage of the whole series about their relationship. Lymond trusts Jerott’s loyalty and friendship but he also values his moral judgement. He know that his own world is one of lying and deceit, politics and deals, and that it is easy to lose sight of the core values that he seeks to live by amongst all that – particularly in his battle with Gabriel where impossible choices may have to be made, and eventually are. Jerott’s straightforward approach gives Lymond a perspective that he could so easily lose otherwise.

In Checkmate Jerott almost gets a hug! – after the initially unrecognised Philippa kisses him:

‘You’ve certainly frightenened him silly,’ said Lymond. ‘If you open your fingers, he’ll drop like an egg to the paving.’ He came forward, and as Philippa retreated, took Jerott lightly by the shoulders. ‘You will have to suffer the same from me,’ he said. ‘It is a forfeit we exact from all bridegrooms.’

It had never happened before. Jerott received the swift, insubstantial embrace and then found that Lymond, stepping back, was looking at him with amiable satisfaction.

After seeing Khaireddin for the first time, seeing Lymond taking opium, and having a knife thrown at him, he is initially appalled but adapts quickly and positively. And receives what for Lymond is effusive gratitude, and then almost uniquely, an explanation.

For a moment Lymond thought, studying him. Then he said, ‘I think you should try to put that out of your mind. You will see me taking it quite often. So long as I do take it you will not, I think, notice much difference. I am not using it to escape my responsibilities, if that was what mainly exercised you. But I should be indebted if you would keep what you know of it meantime to yourself. It will, I suppose, be all too obvious one day, but there is work to do first. Archie is here, and will help.’

‘What can I do?’ Jerott said.

Lymond changed his position, with care, and clasped his hands round his knees. ‘Do you mean that?’ he asked.

‘Of course. You don’t suppose you can do it on your own?’ said Jerott. ‘What can I do?’

Lymond grinned. ‘When the clay for thee was kneaded, as they say,’ he remarked, ‘they forgot to put in common sense.

You may sit there while they bring something to drink. Then you may listen.’

There’s one controversy about Jerott that I haven’t mentioned yet. The accusation that he is physically attracted to Francis and only married Marthe because he couldn’t have him. Having poured over every word written about Jerott I can find no sign of it other than Marthe’s own accusation when they are prisoners of Guzel. I don’t give that any real credence because at the time Marthe is herself very conflicted, hates all men, is bitter that Guzel is casting her off, and is directing barbs at the man who Guzel has suggested as a possible suitor. It plays on Jerott’s mind but only I think because he is horrified at the thought, as he was horrified that Lymond could indulge in homosexual activity with the Aga Morat, even when there was no other choice but death.

Jerott compared to Other Heroes

So we come back to the question – Is Jerott a hero? Well the only way to know is to compare him to some other heroes.

So is Jerott a hero compared to…

Conan the Barbarian

as played by Arnie.

Jerott would run rings round Conan at anything apart from arm-wrestling. Way more intelligent, better soldier, equal bravery and endurance.

Rambo

Sly Stallone.

Pretty much the same. In fact Jerott probably has the edge in emotionally intelligence there!

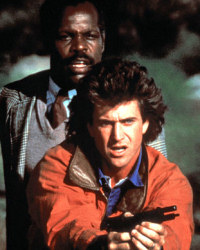

Martin Riggs

Mel Gibson from Lethal Weapon – emotionally wrecked by the loss of his wife. Good close combat fighter. Brave and withstands pain. All pretty equal there.

Humphrey Bogart

Pretty much any character played by Bogie from Sam Spade to Rick in Casablanca. Doesn’t let his feelings out, plays the tough guy but has a heart of gold underneath.

Jason Bourne

Another one that’s a bit screwed up, but is Jerott any less skilled, resourceful, athletic, adaptable? I’d say he comes out of that comparison at least equal.

The Man with No Name

might have the edge in coolness under pressure but other than that he’s mostly just a very good gunfighter. Jerott wins that one for me.

Harry Calahan

Clint Eastwood’s other major character is stubborn and black-and-white in his view of good and evil so pretty similar there. Jerott’s character is much more rounded and developed.

We’ve been gradually raising the bar but now we come to perhaps the two ultimate heroes:

Robin Hood

as played by Errol Flynn

There was only one actor for Robin…

Well, actually maybe there were two

Difficult comparison since Robin is the leader and is really a rather one-dimensional character. Better archer of course, but I’d give Jerott the edge in hand to hand combat. Pretty equal on bravery and athleticism, and loyalty. Military strategy again is pretty equal. Robin’s women are rather less complex so he has it easier there.

But the fact that we can even discuss them together shows, I think, the merits of our man.

Even the “spy to end all spies”, who of course inspired Dorothy, who knew Ian Fleming, to write the “hero to end all heroes”.

James Bond

played by the inimitable Sean Connery

Incidentally some of the younger members of the audience may prefer this version

James Bond – who could be described as another emotional cripple who lost his wife. (Anyone detecting a pattern here?) Once again there’s little to choose between them for bravery or any of the other heroic abilities. Jerott would drink him under the table, though he probably wouldn’t touch Vodka Martini! Only on political complexity and success with the ladies would James have the upper hand. But often he survives by gadgets – Jerott survives by his own wits and skill.

Notice that none of these heroes are perfect, far from it. They all have major character flaws and weaknesses so there is no reason for us to expect Jerott to be perfect. He has his drinking issues – hardly unique in hero land – and he doesn’t understand women, well that’s not exactly unique either in hero land or in real life!

So what we’re seeing is that there’s only one hero that really outranks Jerott…

…and that’s the one in the same books, his dearest friend, that hero to end all heroes.

In a large number of areas Lymond and Jerott are very closely matched. Like James Bond it is Lymond’s ability to understand and pre-empt the political intrigue, the shifting sands of diplomacy and the many shades of grey that exist in the world of rulers and international politics that really sets him apart.

In any other set of books Jerott would be the hero – he’d vanquish the villain and get the girl. His only failing is that he’s outshined by the brightest star in literary fiction.

And of course it is partly Jerott’s hand that frees Francis and Philippa to be together, but at a terrible cost. Had he not held back Richard’s horse might they have stopped Austin from firing the shots that kill Marthe? He’ll live with that for the rest of his life.

Jerott is selflessly doing what all heroes do – putting others first. But in an unusual way. Having seen the nature and depth of Lymond’s despair, and regretting that by saving his life at the Authie he’s forced him to return to it, he is willing to let him go, as Philippa was. How horribly tragic that it costs him Marthe’s life.

Really there is no one word to sum up Jerott’s complex character but the closest has to be that one – Tragic.

I find it a pity, though inevitable, that Jerott is rather discarded at the end of Checkmate but of course the focus is by then firmly on Francis and Philippa and nothing can be allowed to detract from that glorious reconciliation and the revelation of the marriage lines.

Dorothy said that she couldn’t write anything more about Lymond because the gap in the history into which she placed him was closing. We know she went on to write King Hereafter about Macbeth and then returned to the Semples and the Crawfords by an unexpected method. Maybe, if things had been different, I wonder if she might instead have written the ongoing story of her other hero – Jerott.

Our own Simon Hedges thinks that he maybe goes back to Malta, as is hinted at in the end, and dies in the fighting there, and that’s quite possible. But I really hope not. After all he was coming to Scotland having apparently lost Marthe anyway, so why change now? Scotland needs good men, and once before he was going to leave Lymond and changed his mind at the last minute.

I want Jerott to find his own place in the world and find that happiness that Marthe’s death has denied him. The Dame’s pronouncement should not “debar him from love”.

Real heroes deserve more than to ride into the sunset alone, and I have no doubt at all – Jerott is a real hero.