A while back I was re-reading Game of Kings for the Edinburgh discussion group, and thought, not for the first time, to take a closer look at the geography of that lovely passage introducing us to the hopelessly romantic 13-year old Agnes Herries, and giving us a glimpse of Richard’s wry sense of humour. In doing so I realised properly a couple of things that had lain at the back of my mind on previous readings, and was led into a little investigation.

Let’s firstly take a look at the placenames mentioned and see if we can trace a few things about Richard’s journey. All is not quite what it seems, even when you think you have some knowledge!

Incidentally, isn’t the first line of the chapter classic Dorothy?

On Sunday, the day after the affair at Lake of Menteith, Lord Culter was also taking aquatic exercise of a kind which all but turned his epithalamics into elegies.

How many of us had to look that phrase up to make sure we understood it? 😉 It could have come straight out of Lymond’s verbal extravagances.

Richard has been in South-west Scotland with a small harrying force taking advantage of Wharton’s retreat and then trying to convince some of the border families who are being hard pressed by the English to remain loyal to the Scottish cause. We are told that he’s had a fair degree of success and it appears that he has considerable powers of political persuasion as well as practical military leadership. How skillfully she builds up our knowledge of him without resorting to simple direct description.

He is on his way back home when he remembers that he has an escort task to undertake and

“…turned aside at Mollinburn with six horsemen to ride through the Lowthers to Morton.”

So our first task is to find Mollinburn and get ourselves oriented. This proved harder than expected as both Google and Bing are not great on Scottish minor placenames. I found a Mollinsburn, but it was much too far north – north-east of Glasgow in fact (which would confuse me further later on). I knew roughly where the Lowthers (a range of hills) were, though it was a very long time ago that I had once walked there and my memory of their precise position was sketchy.

Being in Slovenia with no access to my collection of paper maps back in Edinburgh I had to rely on the online variety, but it’s far harder working on a relatively small screen than a map spread out on a tabletop. Most online maps are lacking in any sort of detail even when you zoom in and out. Bing has a bit more detail than Google but here I was at first misled. I found Lowther Hill and Green Lowther but they’re quite far north – beyond the A702 road towards Wanlockhead – and I coulldn’t work out why Richard would have gone that far north and then back south for his meeting. However while casting about for further information I came across an inset online version of a Bartholomews map. Bartholomews are an old Scottish firm of map-makers whose maps, while lacking some of the fine detail of the Ordnance Survey, were excellent for visualising an overall area or trip and tended to give prominent names to ranges of hills rather than naming all the individual ones. On that map the Lowthers were indicated in two sweeps – a long one running NNW and a shorter one running NNE and forming a V shape starting much further south than the individual hill from which the name comes. So I had a bit more to go on but still could find no sign of Mollinburn.

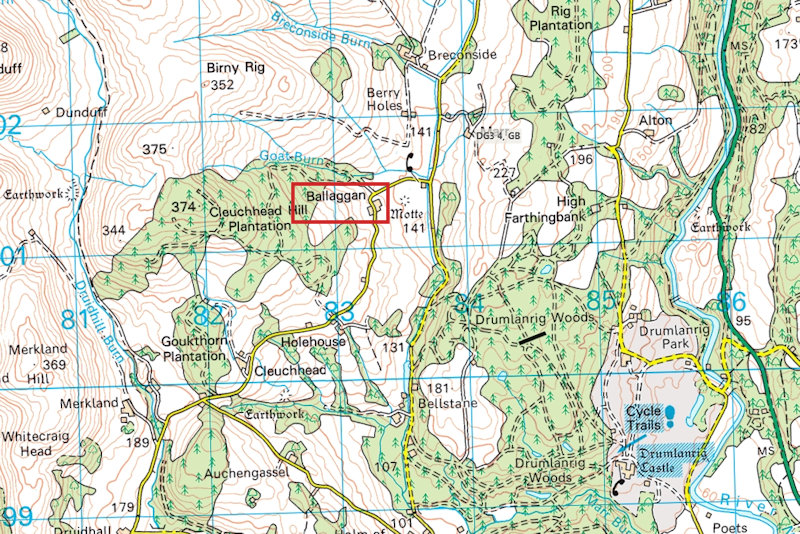

At that point I switched back to Bing. If you are set in Bing as being in the UK then you have a very useful faciity invisible to everyone else – at certain magnifications you get the option of viewing UK Ordnance Survey maps which are superbly detailed and the must-have map for hill walkers. I started looking on there and after a lot of scrolling around I found Mollinburn – not even a hamlet but merely a house just off the A701 road which runs between Dumfries and Beattock; about a mile south of the village of St Ann’s. So we have a start point. Now for the next named waypoint – Morton.

Again the search engines are useless – no sign of Morton. So it’s a question of looking to the next named place and trying to work back from there.

On Sunday afternoon, the party he was expecting came in from Blairquhan, and he left Morton on the Sanquhar road to take the Mennock Pass north.

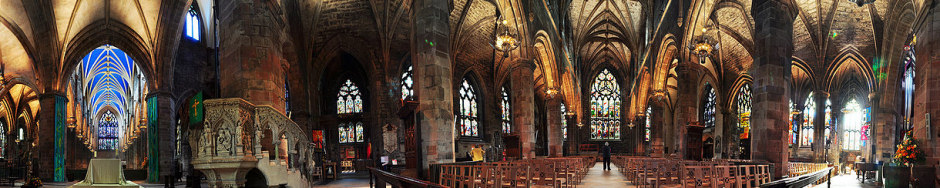

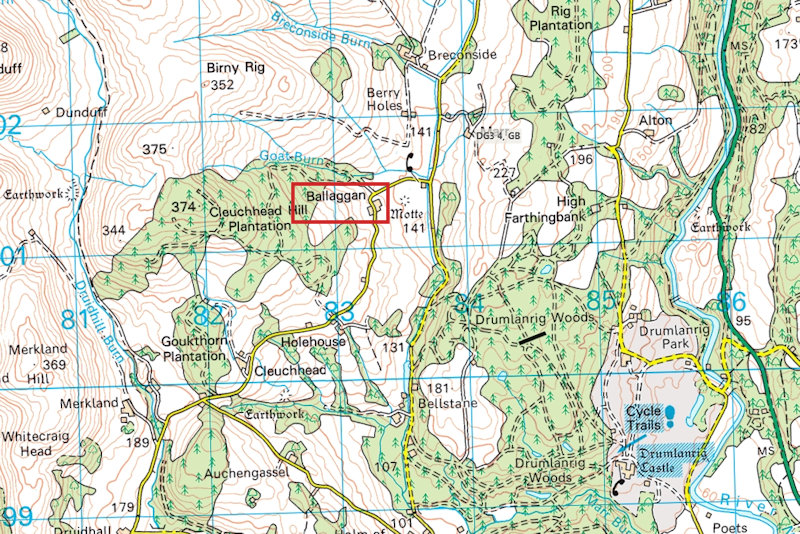

Sanquhar is much easier to find – it’s a village away to the north-west on the A76 – and pulling back south you find Mennock which marks the entrance to the pass running north-east. So Morton must be somewhere on the road south of there. Sure enough, detailed perusal of the Ordnance Survey maps brings up the ruins of Morton Castle, situated above Morton Loch about ¾ mile east of Carronbridge on the A702, and with a few other Morton related names around it. It was built by the Earl of Morton who was a Douglas, and just across the valley to the west is that other Douglas stronghold, Drumlanrig Castle, of which more later.

We can now see that Richard rides across the southern slopes of the Lowther Hills from Mollinburn; either heading northwest and then west and skirting around the Forest of Ae, or going through the forest to begin with, though there’s no obvious path visible now. Whichever way it was the riding must have been rough and we can admire the stamina of the riders. He had started north on the Friday so I would imagine he probably stayed the night somewhere around Morton before meeting the party bringing Agnes on Sunday.

Here we must also look at where they were coming from. On previous reads I had rather lazily mentally assumed they were probably coming from around Terregles, but the text tells us explicitly if we care to check and given the recent English advance it then makes perfect sense. They were coming from Blairquhan where Agnes’ grandfather is based and we must assume that she was moved there to avoid the danger of being taken for ransom.

Blairquhan is about 40 miles to the west in South Ayrshire so a decent length journey on horseback just to get to the meeting with Richard. We know that he and Agnes are now heading for Stirling to join the court who have retreated there for safety after the eastern English advance towards Edinburgh. Morton to Stirling is another 75 miles, which again gives us pause to consider the problems of travelling in those times.

After a diversionary description of Agnes and her romances we come to the meeting with Dandy Hunter. Initially it’s not clear how much further we have travelled and on my earliest reading many years ago I initially assumed we had gone a considerable distance. The reason behind this was that I’d heard of Ballagan, the name of Dandy’s estate, and knew it was near Strathblane in the Campsie Fells, between Glasgow and Stirling. That seemed to make sense since they were headed to Stirling. However at this point things start to get geographically confusing and I realised I must be mistaken, though it was only now that I got around to resolving the matter properly.

Look,” said Hunter. “We’ll drown if we exchange news here. Come with me to Ballaggan – you could do with something hot inside you anyway.

Suggests they must be close to Hunter’s house…

But again, they had halted. The Nith, which lay between themselves and Ballaggan, ran unusually fast and high at their feet, and an outrider who drove his horse in at the ford thudded out again, wet to the stirrups.

Hang on! The Nith? That’s the river that runs from west of Sanquhar, turns south down the valley through Morton and down to Dumfries, then on till it empties into the Solway Firth. If we’d gone through the Mennock Pass we’d have left it far behind, so if we’re crossing it then we must still be in that valley and not have gone very far at all. And if that’s the case Ballaggan should be to the west of the river since Morton is on the east side.

And of course after the near disaster crossing the river they’re taken to Drumlanrig, because it’s nearer! (Slaps forehead!)

For they were in a Douglas household, instead of Hunter’s elegant, exhausted estate of Ballaggan. Alone and without help, Richard had brought Agnes Herries ashore: his own men were upstream and Andrew Hunter, far ahead, had been deaf to his shouts. But afterward, warned by the commotion, he had raced to their aid, wrapped the girl in his own cloak and carried both swimmers to Drumlanrig, the cavalcade following. Ballaggan was nearly an hour’s journey away and could wait. These two could not.

So, clearly the Ballagan I knew about away to the north cannot be Dandy’s place. Hmmm, wait, there’s two g’s in Dorothy’s version and only one in the Strathblane name! On its own that’s not a certainty since spelling in those times could be so variable and often changed over the years, but the geography is surely decisive. But searching for Ballaggan just seems to bring up Ballagan. Google knows best even when it doesn’t.

At this point I’m beginning to think that maybe Dorothy borrowed the name and tweaked it; maybe this Ballaggan is fictitious like Midculter and Flaw Valleys. No, that’s not her way. It must be based on something more.

Back to the maps. West of the Nith, north of Drumlanrig, south of Mennock. Nothing on Google – hardly anything named at all in that area on either normal map or aerial. Same with Bing.

An hour’s ride – how far can a horse travel in an hour – 8 to 12 miles apparently.

Comparing the two more detailed maps, Bartholomews and Ordnance Survey, you’d barely think you were looking at the same area. Hmmm just found a place called Buck Cleuch – could it be the place of the legend – of the Scott who saved the King from a stag and was known thereafter as Buck Cleuch, later Buccleuch. Seems a bit westerly but who knows? It might be. But actually, maybe I am too far west myself, back up a bit towards the river, and change the magnification so we get more detail.

Come on man, you’re a search specialist, let’s delve a bit deeper and stop accepting what Google thinks we’re looking for. A bit more digging and we find a Ballaggan Cottage, the right spelling, Marrburn, Thornhill, Dumfries and Galloway, so it’s the right area, “within walking distance is Drumlanrig Castle”, surely we’re on the track now. “2 bedroom cottage situated within the Buccleuch Estate”, so these were Buccleuch lands – maybe that is the place of the legend.

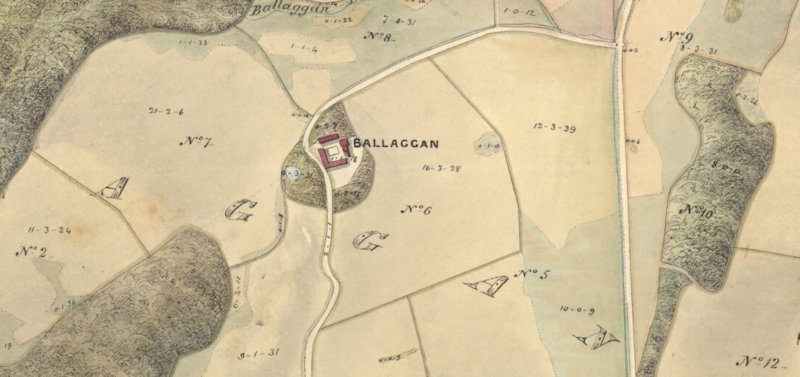

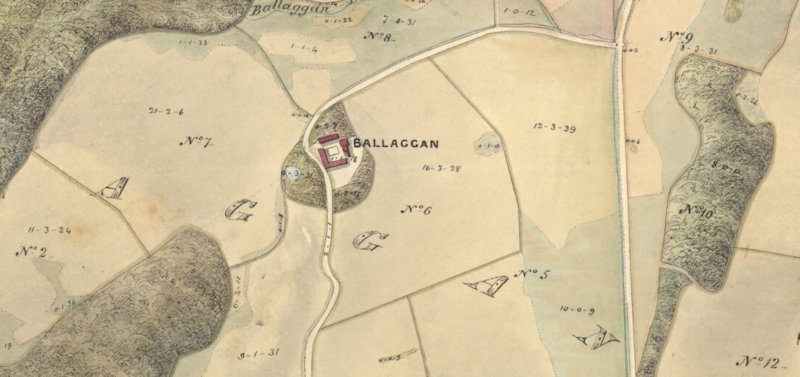

A bit more searching… Gotcha! National Library of Scotland, Estate Maps of Scotland, 1750s-1900s, Breckonside, Marr, Ballaggan. Queensberry Estate Plans, 1854

Volume 3. Courtesy of Buccleuch Estates.

Here’s a look at the whole map first

It looks beautifully hand-drawn but then you realise you can zoom right in.

Looks fairly small, and like more of a tenant farm than an estate, so maybe Dorothy was exaggerating or maybe it was bigger in earlier times, but we’ve found it; she did base it on a real place. Of course she was friends with the Buccleuchs so I wonder if she saw this original map that that is now digitally archived to the NLS, during a visit. Would be lovely to think so. You can view the map yourself at https://maps.nls.uk/view/129393259

Now, final task, relate that to the modern maps, adjust the magnification again and there it is. So obvious when you know where to look 😉

Well, after all that I have considerable respect for Richard and Agnes for their riding ability – a 13 year-old riding 115 miles, much of it over rough ground, to visit the court has a lot of grit.

And who would have thought that Dandy Hunter and his estate would turn out to be not quite what he appeared?!

Amazing how much investigative fun you can have with one small passage. Another toast dear lady! And I hope they have Talisker in heaven.